When is an in-crop fungicide worth it?

This article was originally published in Better Farming Prairie Agriculture May/June 2020 Edition

You have thoroughly vetted your agronomy checklist. You have accounted for seeding rate and seed quality, variety selection, fertility, and rotation. You have set the foundation for a strong, healthy crop.

However, the risk of disease effects on crops remains. Certain diseases can be present in your crop residue or soil, wind trajectories from the Prairie Pest Monitoring Network in previous years indicate stripe rust can be a risk, and your provincial Fusarium head blight (FHB) risk map may indicate high risk later in the season.

In practical terms, farmers in Western Canada use three in-season fungicide timing opportunities: herbicide, flag leaf, and head timing.

I will be blunt about herbicide-timed fungicide applications. No yield or disease-control advantage exists for applying fungicide at herbicide timing, research indicates.

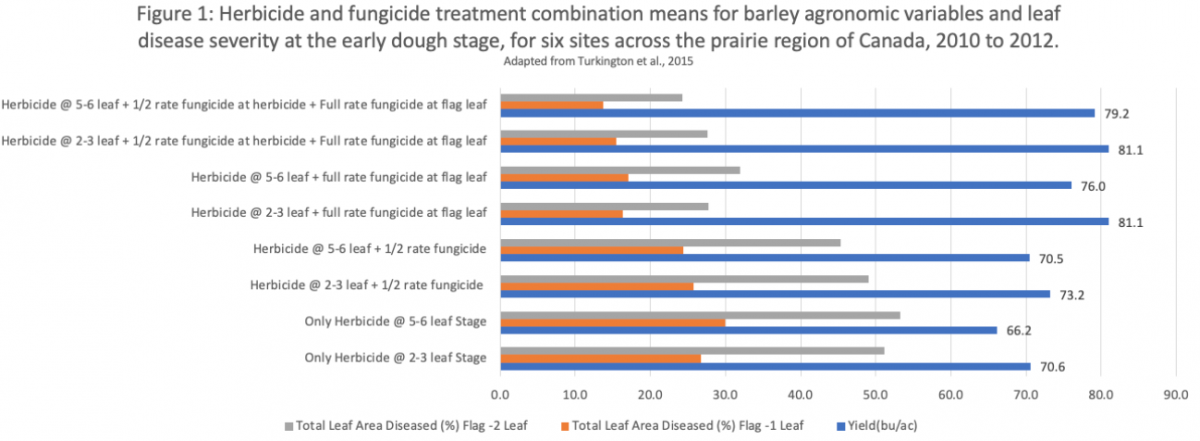

Dr. Kelly Turkington, a plant pathology research scientist at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Lacombe, Alta., and other collaborators in six locations across Western Canada studied these types of applications on spring barley. AC Metcalfe demonstrated no benefit of herbicide-timed fungicide applications on yield compared to a flag leaf fungicide application alone. (See Figure 1)

Delaying herbicide applications with the goal of timing herbicide and fungicide tank mixes closer to flag leaf emergence only resulted in increased weed competition and decreased yields, Turkington and his collaborators found.

Data for this graph courtesy of Mahnoor Asif, a M.Sc. candidate working with Dr. Sheri Strydhorst.

The concept of applying a fungicide at herbicide timing is to reduce the early-season leaf disease that may have increased potential to affect the yield-bearing leaves, such as the flag and penultimate, and to potentially save a sprayer pass.

However, Turkington and Strydhorst’s research, along with other studies, has indicated that this situation is not the case. Outside of having no benefit on yield and profitability, early-season fungicide applications increase the risk of unnecessary selection pressure leading to eventual fungicide resistance.

Removing early fungicide applications from the toolbox leaves us with flag leaf and head timing for fungicide applications.

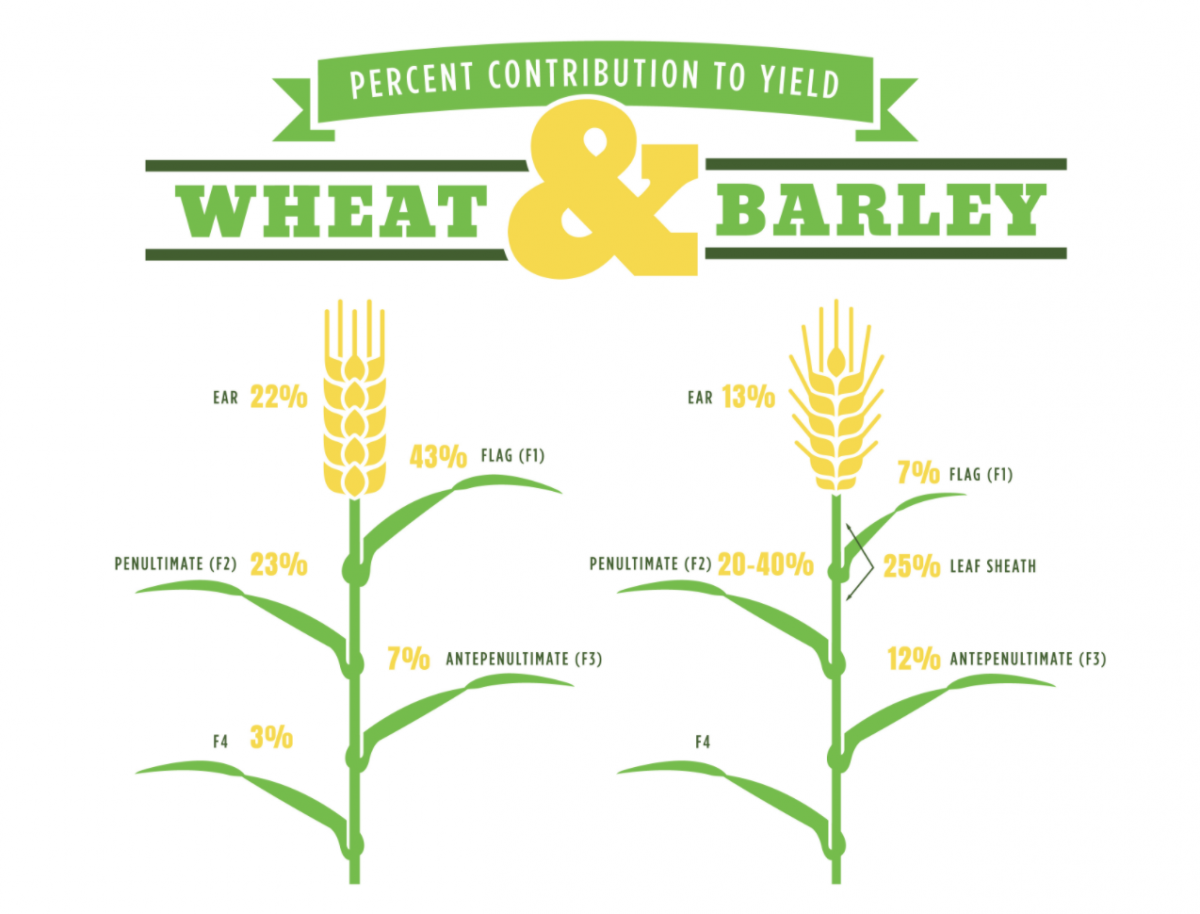

Flag leaf timing for fungicide applications has been well documented. Such applications provide yield increases to both wheat and barley when disease is present and environmental conditions are conducive for disease proliferation. This information should come as no surprise as the timing of this application looks to protect the flag leaf and penultimate leaf, which are the two leaves that contribute the most to yield for wheat and barley. (See Figure 3)

When disease is present in crop residue and environmental conditions are conducive, the disease will spread quickly through the crop canopy. Disease infection will limit the plant’s photosynthetic capabilities, increases plant stress, and requires resources to help with plant defense. This situation pulls energy from where it is desired: yield and quality development.

(Figure 3): This image shows the percent contribution of each part of the plant to the yield of wheat and barley.

If we know protecting those yield-bearing leaves is important, under what circumstances should we spray a flag leaf fungicide? This question is not an easy one to answer as differing farm management strategies will dictate disease risk. Each disease also requires management at different thresholds.

We are all familiar with the disease triangle: host, disease, and environment. These factors all play a role in disease risk.

For example, a variety with a weak disease package, in short rotations, and a field with recent history of disease issues put you at higher risk of disease proliferation. In this example, your host is weaker and disease is likely more abundant due to short rotations.

However, environmental conditions must also be conducive for disease growth. Even if the disease is present and the host is susceptible, moisture is needed to create an environment for disease to grow. This point could be rephrased as: how much rain and/or moisture is needed to warrant a fungicide application?

Strydhorst recently conducted research on AC Foremost (an older cultivar with MS rating to leaf spots), looking at different rainfall and fungicide timings. She completed this work between 2014 and 2016 at Lethbridge (irrigated), Lethbridge (dryland), Killam, Bon Accord, and Falher. Those locations which received greater than 4.5 inches (11.4 centimetres) of rainfall between seeding and flag leaf emergence displayed a yield response to flag leaf fungicide applications.

However, as much as this research indicated a rainfall threshold for response, actual response of the crop to fungicide at flag leaf may vary from that threshold depending on the year, variety, and other management factors mentioned above. Therefore, this value should only be used as a rough guideline.

Rainfall accumulation will never replace thorough field scouting for risk assessment. Monitor rainfall as an indicator but do not have it replace in-field inspections.

Remember, fungicides are preventative rather than curative. So, fungicide applications must be made prior to extensive symptom development to maintain leaf photosynthesis. For stripe rust, it is typically recommended that fungicide applications happen prior to 5 per cent leaf coverage as rust reduces yield much quicker than other foliar diseases.

For wheat (tan spot and Septoria) and barley (net blotch, scald, spot blotch) leaf spots, Turkington suggests observing what the crop is telling you and using scouting as a key activity.

Earlier in the growing season, note developing disease when scouting for weeds. If symptoms are easily found, this information would suggest a developing risk that may warrant a future fungicide application. Follow this up by scouting again as the crop starts stem elongation and as the top three canopy leaves emerge.

At this stage, if leaf disease is well established in the lower canopy with moderate levels (>10 to 20 per cent leaf area affected) and it is easy to find symptoms in the middle part of the canopy with levels starting to approach 5 per cent of leaf area affected, a fungicide application is likely warranted.

Turkington and colleagues have conducted some work trying to relate barley disease levels around flag leaf emergence to levels of disease in late July and early August. Based on this research, if more than 1 to 2 per cent of the area of the third leaf from the head is affected by disease at flag leaf emergence, then a fungicide application is likely warranted. A similar approach can likely be used for wheat.

However, given that the second (penultimate) and third leaves from the head are more important in barley yield (Figure 3), it may be beneficial to look at a fungicide application slightly earlier than flag leaf emergence. For example, if significant levels of disease have developed in the lower canopy and signs indicate it is moving into the middle canopy, then a fungicide application may be needed when the penultimate leaf is emerging.

If disease presence is limited in the lower, middle and upper canopy as the crop progresses from stem elongation to flag leaf and head emergence, and environmental conditions are not conducive for disease spread from flag leaf to head emergence, likely no benefit exists to spraying at that time.

This discussion leads us to head timing fungicides.

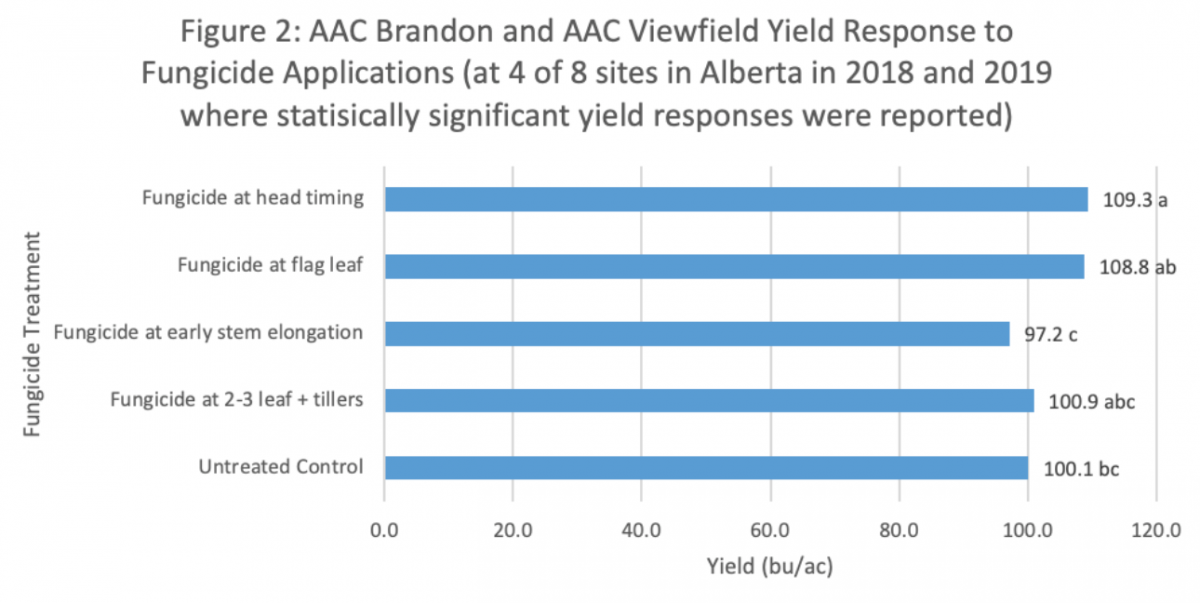

Interestingly, in the 2014-16 trial mentioned above, Strydhorst also compared flag leaf to head timing application. Results demonstrated the same, or greater, yield responses to head-timing fungicide applications as compared to flag leaf applications.

Even under conditions of 4.5 in. (11.4 cm) or greater rainfall from seeding to flag leaf emergence, head timing fungicide applications provided the best response. This information is beneficial for growers challenged with the dilemma of applying fungicide at the flag leaf or at head timing.

Dustin Eric MacLean, an M.Sc. student at the University of Saskatchewan, found similar results when he compared flag and head emergence timings in spring wheat for leaf disease management.

However, Turkington cautions that delaying fungicide applications until head emergence may result in a reduction of the level of leaf disease control, but only when you have extensive disease development occurring as the crop progresses from stem elongation to flag leaf emergence.

Turkington also observed this in an earlier barley trial in the late 1990s or early 2000s[1] where the level of control with a single-head application timing started to drop compared to a flag leaf timing. Researchers also observed this result in a new barley cluster funded trial looking at post head emergence timings to improve FHB control.

In both situations, when leaf disease is already well established in the upper canopy as the crop moves through flag leaf emergence, the level of control from a single-head emergence fungicide application may be reduced. In this situation, a fungicide application around penultimate leaf to flag leaf emergence may be needed followed by a second application at head emergence to top up the level of leaf disease control, while providing some FHB suppression.

Keep in mind that distribution of the 4.5 in. (11.4 cm) of rain is important as well. If all that rain fell very early in the season and conditions were dry afterward, you may see less disease growth as compared to that 4.5 inches being distributed every few days over the same period.

- Mitigate disease risk through a strong foundation of agronomics including variety selection, longer and more complex rotations, seed testing, and fertility management.

- It is very unlikely that an herbicide-timing fungicide application will provide payback. Delaying herbicide to include a fungicide may reduce yield due to increased weed competition.

- Rainfall and environment play an enormous role (of course!) in disease risk and effects. Total rainfall above 4.5 in. (11.4 cm) between seeding and flag leaf emergence can be a general guideline to assist in fungicide spray decisions.

- But do not spray based on rainfall accumulation alone! Align recognition of increased disease risk due to rainfall with thorough field scouting to determine the best course of action.

- Delaying fungicide from flag leaf to head timing can provide equal, or even better, results than flag leaf timing. However, this information does not mean you should avoid scouting for disease prior to flag leaf timing. Certain environmental conditions and diseases such as stripe rust may still warrant a flag leaf fungicide application.

- Significant leaf spot or rust development prior to flag leaf emergence may mean that you need to apply fungicide when the penultimate leaf and flag leaf are emerging, followed by an application at head emergence.

- Use disease-monitoring tools such as your provincial Fusarium risk maps and the Prairie Pest Monitoring Network.

[1] This 2015 report was based on 2010-12 study data: Turkington, T.K., O'Donovan, J.T., Harker, K.N., Xi, K., Blackshaw, R.E., Johnson, E.N., Peng, G., Kutcher, H.R., May, W.E., Lafond, G.P., Mohr, R.M., Irvine, R.B., and Stevenson, C. (2015). "The impact of fungicide and herbicide timing on foliar disease severity, and barley productivity and quality.", Canadian Journal of Plant Science, 95(3), pp. 525-537. doi : 10.4141/CJPS-2014-364